My Wife Has Breast Cancer.

We know there is suffering going on around us. Print media, television and the internet provide a steady stream or steady multiple streams reporting every imaginable human agony. And the images are right there before us, leaning into our faces.

Images of terror and horror stack up in our brains. In our minds, we can reach out and touch faces distorted by grief and shock. Yet, no matter how deeply we empathize, and we do, other peoples’ sufferings are over there, across town, around the corner. If we care, we’re fortunate because not to says something about us we are not eager to consider. That is until.

Debo and I were excited that Thursday evening last October, the night before we were to fly out the following morning to Boston. She had been invited to bring two of her Stellarella children’s books (books for little progressive readers) to the fair and meet other authors, publishers and book hounds. We finished packing our suitcases and walked into the great room for a drink. Then she looked at me and patting the sofa beside her, said, “Come here and sit down. I want to talk to you.” I was instantly on alert. But in no way prepared.

She looked at me and said, “I think I’ve found a lump in my breast. It’s not big, but something’s there. Here, give me your finger.” She took my hand and guided my fingers to the spot on top of her left breast a few inches above the nipple. She was right. It wasn’t large; not particularly scary, but it was very there.

You know how you can scream and shriek inside your own head when something is said to you that’s unthinkable? That’s exactly what happened. She said, “I think I should go see Barbie (her GYN).” “Yeah,” I said, “email the office right now and get an appointment.” Debo said, “You know, it may be nothing, a cyst or something.” “Sure,” I said, “but it’d be better to know.” She sent the email.

Later we got in bed, and as usual, our hands found each other under the covers. Our fingers were anxious to assure each other that everything would be okay.

Getting up early the next morning, we collected bags and headed for the airport. Just after we landed in Atlanta, Debo opened her computer and said, “They’ve already responded. Got an appointment next Wednesday at 10.” “Great,” I said. “Thanks for doing that.”

Boston was wonderful. Debo and I don’t take bad trips. Maybe it’s our age, the years together, trying this and trying that. Point is, we always have great trips. Looking back, it amazes me that we had such a great time when that appointment hung in the air – like an empty box on a string; clearly there but without content.

Returning home late on Monday night, we fell into bed, exhausted. On Tuesday, we went in to the office and worked with Jennifer making sure our upcoming trip to Houston would not only be fun – we would spend two days with grandchildren, Poet and Violet – but we would get some good business done with close colleagues there.

The plan was to pack that night for pleasure and business, pick up the rental car the next morning, go to Debo’s appointment with Dr. Sullivan and then hit the road for Houston.

Next morning, Dr. Sullivan felt the lump in Debo’s breast, rolled her stool back from the examining table and said to Debo, “Do you want me to call Anky?” Anky is the affectionate name of our friend, Dr. Anthony Petro, brilliant surgeon and sage of medical practice and wisdom. Debo said, “Yes”- her voice increasingly strained with apprehension.

Drs. Petro and Sullivan conferred and sent us immediately downstairs to the Center for Breast Health where Debo was to get both a mammogram and a biopsy.

As we rode the elevator down to the first floor of Baptist Hospital in Jackson, we both were still hoping that the results of the two procedures would be negative for cancer.

We were told we’d get results in 24 hours. An appointment was already scheduled with Anky (Dr Petro) for 10 AM the following morning (Thursday). So, the following morning we’re sitting in Anky’s office as he tells us that the results of the two procedures came back positive. Debo asked him, “You mean I have cancer?!!” “Yes,” he said, “I’m sorry. What do you want to do?” Debo was shaking her head, “No, Anky, that’s not the question. The question is, “What would you do if it were Maryanne?” (Anky’s wife and our dear friend) Anky said, “I’d get that shit out of there.” Debo said, “OK, let’s do it.” I set up a refrain, “Let’s do it!”

In those minutes, I saw Debo, my bride, my partner, my life outside me, curl into a ball on the examining table weeping and shaking. Everything slowed down to a crawl. I stood there holding her hand and holding on with all my might, barely able to keep from breaking down. She was terrified. I was terrified. Our life changed in that instant. Somewhere in our shared life, a great iron bell fell a thousand feet, thudding to the ground and sending shock waves in every direction.

Suddenly I realized that Anky was speaking. As I “came back”into the room I heard him saying, “Debo, you’re going to be alright. You found it in plenty of time. You’re going to be fine.” I desperately wanted to hear him say it but I could not stop my slide into the airless, black hole into which I was falling. “Yes,” I was saying inside my head, “yes, we caught it early; it’s very small; Anky will get it out of there. He’s the best. He knows. He’ll get it out and Debo and I will continue our amazing life trip together.” But, I still couldn’t breathe below the first 4 inches of my lungs.

Anky then explained that a reconstruction surgeon, Dr. Kenneth Baraza, would be doing the reconstruction surgery following the removal of both of Debo’s breasts.

Even though the lump was in the left breast, since Debo’s younger sister, Terry had died of breast cancer 12 years earlier, Anky said Debo should have both breasts taken. Debo agreed. I agreed. Anky asked Debo, “When do you want to do it.” Debo responded without missing a beat. “Tomorrow!” He said, I don’t know if we can get it scheduled that quickly, but we’ll try.” Anky said that he had made an appointment with Dr. Baraza for that afternoon. Remember. It’s still Thursday, October 29.

We left Anky’s office and went somewhere – I cannot remember where – and then showed up at Dr. Baraza’s office at 2 pm. He was very easy to meet. Very kind; very professional, very reassuring. He examined Debo’s breasts and assured us that the procedure was very “doable.” He said that since Debo already had implants that she had had for 25 years, this would somewhat simply the procedure. He went through all the possibilities about skin flaps, possible grafts taken from her back, etc. He said that he and Anky would tag team the surgery and since Anky would do an excellent job, he would have the best scenario to deal with.

I’m skipping a lot of narrative here about the long, long weekend that came next. What I write here is an abbreviated version of a much longer piece. I have a place to go to in this little account and I don’t want to get lost in the thousands of details of our still-in-shock lives over the last five months.

The surgery came and went. Everything – pretty much everything we hoped for – went beautifully. The pathology reports came back with good and yet frightening news. The tumor was only 1.4 cm. Stage 1. It was also grade 3. If you don’t know this language, and I surely didn’t, that means although the tumor was small, it was very aggressive. In the sentinel lymph node, there were two suspicious cells; in the second, there was nothing. I am giving you these details because for people with cancer and their families, these details speak the language of living and dying. It is a foreign language in a new, bizarre land we’ve migrated into overnight and we strain to master it. As aliens living in a strange new land, we are afraid we’ll misunderstand what we’re told and fail to do something we should or make a wrong choice.

Debo and I have been living in this alien place for months. She’s now had her third treatment, “infusions” they call them, where for hours she sits in a big chair and poisonous drugs are dripped through a “port” in her heart’ssuperiorvena cava– Taxatere – Paraplatin – Herceptin.

The side effects come and go; some severe, some less so. Headaches, nausea, bone pain, neurapathy (burning, itching, swelling of hands and feet) and bouts of sleeplessness augmented by days of drugged exhaustion. Debo “knows” it will soon be over; still, she wonders some days, “Will I ever feel normal again?”

Yet she doesn’t complain; doesn’t rail at the unfairness of it. There were brief periods of depression and terror in the interim between surgery and the beginning of chemo.

She dreaded losing her hair. During that period, I saw in bold relief how we burden women and girls with the constant insistence that they look good, dress “right,” and that their hair be stylish. Then, when they are the most vulnerable to the very real fear and dread of cancer, they experience themselves as “disfigured” and no longer desirable. I’ll say this much. Her fears could not be further from the truth.

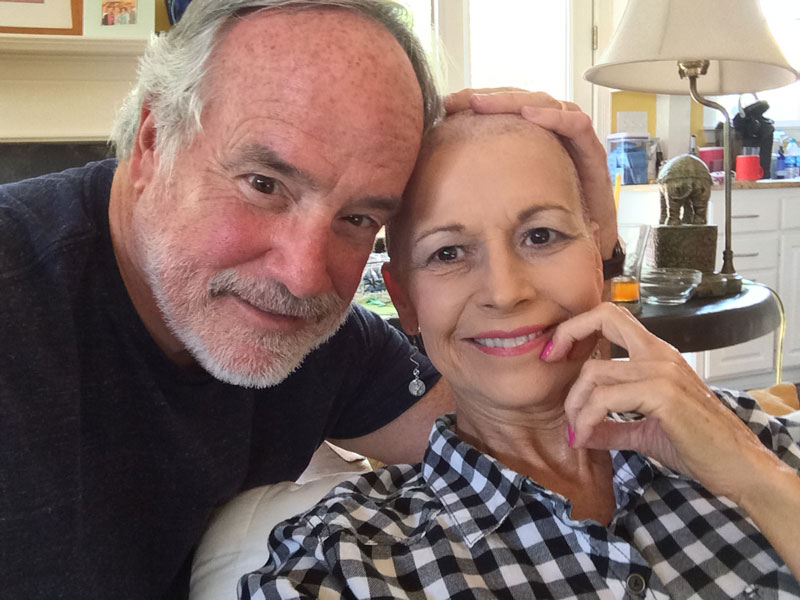

This will sound silly and superficial but I want to say it. I sit beside her on the sofa,

her now bald head resting on my shoulder and I understand that this is Debo, the real Debo not that the dynamo woman with beautiful hair is not. But this Debo is stripped down to the bone. And never as precious or as beautiful as she is now.

The spirit of life that beats in her great, great heart and through those big, brown – almost black eyes – tells me here is a human being infinitely worth spending my life with come what may.

When we lived in Colorado all those years, we loved to backpack. We learned about hiking and climbing. We learned that on the steepest ascents, we would sometimes have to take an upward step or two, then stop and rest before moving on. We learned to keep putting one foot in front of the other one. The reward waiting for us at the summit were vistas of the Rocky Mountain along the Gore range that took our breath away and sometimes made us cry.

We remember the lessons of that climbing experience. Now, to our astonishment, as we move through the days together – Debo carrying the burden of the debilitating side effects, me climbing along ahead or behind her, absolutely helpless to fix it or make anything “go away – we see the amazing beauty of life’s million gifts that come to us on a daily basis.

Family and friends scattered across the country began praying for us on Thursday, October 29 and haven’t let up. “We love you and we’re praying for you,” they said. Hospital admissions people, nurses, custodians, coffee shop attendants, therapists, technicians — giving us compassion, giving us prayers.

Honestly, I’ve had and still have a lot of trouble with prayer. Of course, when friends and loved ones face hardship or loss, we say, “We’re praying for you.” And it’s never been a lie; but so many, many times I was not sure what I was saying. Because I clearly did not mean the same thing as people do when they say, “Well, I was late to the parent-teacher conference and I prayed, ‘Lord, please help me find a parking place. Andheshowed me one right in front of the school.'” And, I simply refuse to believe that God keeps a six year old child on the third floor alive through the threatening illness and let’s the seven year old on the floor above die. I’m a progressive for God’s sake.

Yet, through all the prayers — all the prayers, Debo and I have come to know this. Whatever prayer is, whatever else it is, it is love unapologetically expressed. Not the prayer of easy assurance, but prayer where the one who prays invests herself in your welfare and the welfare of your family. God cannot reward one and punish another. Were God to do that, God would not be God. Whatever god is and I know a gillion things god cannot be – whatever god is, beneficent intelligence in the universe, whatever; human compassion, the capacity of human compassion in this end of the cosmos, aggregates and effects the cells of brains and bodies and souls.

But healing flows from prayer. Genuine prayer get’s amplified by other genuine prayer. And I’ll take prayer on Debo’s behalf, even my own behalf from anyone anywhere, anytime.

Debo and I share the vista of three more rounds of chemotherapy. It will go as it will go. Some days it’s way harder than others. One foot in front of the one before.

What’s my point? The point is that empathy and compassion give life, life. Certainly here, now. Conceivably beyond now. Our forebears prayed for the departed. In many instances, they were praying for the salvation of those gone before. I can’t do that.

But Debo’s suffering, my own, make me want to embrace all who suffer or who have suffered. In these moments, old angers, resentments, attitudes toward and about people melt away.

Now what is that about?